The Poetics of Grief

Listening to Pattern in Jenny Schwartz's God's Ear

This piece was created for the Vineyard Theatre production of God's Ear as part of THE PROGRAM, a joint effort with Helen Shaw and David Cote of Time Out New York. Armed with pre-show discussions and supplementary dramaturgical materials, THE PROGRAM roams from theater to theater, providing context to audiences at selected experimental productions. Our goal is to make the widest possible audience feel welcome at the widest range of dramatically ambitious work.

We’ll get to what actually happens in this play in a moment. But it isn’t giving much away to reveal that God’s Ear takes place in the aftermath of its principal event—the death of a child—and that its subject is grief.

Grief turns out to be a tricky subject for the theatre. Moving laments are common onstage, yet bear little relation either to the events or the experience of actual loss and grief. They undoubtedly represent what we would like to say under the circumstances, yet few of us are afforded an opportunity to throw ourselves on a bier. For most people, the events following a catastrophic loss are little more than the routines of everyday life.

These routines, however, are utterly transformed by the experience of an acute—and agonizing—form of clinical depression. Time stands still or moves in torpid loops; human interactions all feel flat and fake; inside one aches and at the same time feels paralyzed and numb, listless, exhausted. Meaningless thoughts chase each other to no purpose, while speech requires so much effort that it easily becomes rote, mechanical, affectless. An honest depiction of ordinary, devastating grief thus cannot rely on events alone without introducing “theatrical” moments—stagy confrontations, revelatory breakdowns and so forth. Good drama, perhaps, but dishonest. As for depicting the experience of grief, that would seem quite literally beyond the scope of expressive language.

Virtually everyone who’s written about this play has noted how the dialog has been built out of clichés (I am going to use the term “catch-phrase” instead, to avoid the other meaning of cliché as “stale and formulaic description.”) Many often point out that the dialog is rhythmical, too—almost musical. But in fact, Schwartz has developed this highly-structured language and syntax—a kind of verse, really—as a radical way to depict, and recreate, the experience of grief. And as with any verse, listening requires a shift of appreciation that include the rhythm and pattern as much as the literal sense of the words themselves.

Patterns and Speech

When we hear a catch-phrase, we automatically understand that the words are not original with the speaker. They have not been not thought up in the moment; they don’t take that much effort. When we hear, or overhear, an exchange of catch-phrases, we likewise realize that conversation has been reduced to an exchange of tokens.

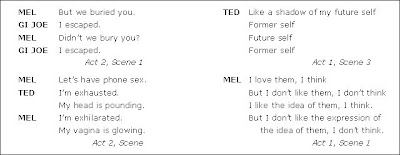

This is still a conversation—information is still being exchanged—but the amount of information is far less than the verbiage required to convey it, and the words themselves are little more than a form of decoration, a deliberate distraction from the underlying poverty of the coinage. Finally, when speech is reduced entirely to catch-phrases, we experience a form of entrapment. The sentences can only end in one way—pigs can fly, but not soar; cows come home, but not back—and as the phrases pile up we experience their deadening predictability. Schwartz however counteracts this fundamental regularity by overlaying a tracery of pattern:

This is now recognizable as poetry: a quatrain in which a matrix of repeated words (“and”, “that”) contains a shifting set of terms (“bridge”, “cross”), using the rule that the second term in the lead phrase moves to the first term in the following phrase. The effect of this rule is to use the deaden-ing conclusion of each catch-phrase as a springboard for the next, thus introducing (along with the perceived positional shift of the terms themselves, from 2nd to 1st) the illusion of forward motion.

Patterns and Loops

In order to really understand what Schwartz is doing with language, we must first understand more about her use of pattern. The simplest form of pattern is repetition:

Literal repetition creates the experience of being stuck in time—which, unfortunately, isn’t parti-cularly dramatic, and if sustained soon becomes excruciating. The repetition of alternating phases, however, makes a Loop, which is sustainable. The effect is not so much being stuck as hovering in time, circling around and around—dithering. One might also say, “echoing:” hearing apparent responses where there are none, the sound of another’s voice when there is only one’s own.

Loops of all kinds appear in this play, from simple loops in which a minor variation is introduced on the second pass:

To loops in which the starting point alternates between the speakers (technically known as a “phase shift”):

As noted, another common device is the Reverse Loop, in which the second pass contains a negation or reversal of the first:

Naturally, it is also possible to flip and reverse (a device which classical rhetoricians loved so much they named it the chiasmus, or “criss-cross”, but we can refer to as a Flipped Loop):

Yet another way to build up patterns is through Concatenated Loops, in which new elements are inserted into the base phrase with each new pass:

There are also loops which count up or down (Enumerations) and loops which build up lists of similar terms (Elaborations). All these advanced loops, which depend less on literal repetition and more on perceiving relationships, approximate the experience of completing an essentially meaningless task. Note too, how within each list repetitions of individual words and word pairings (“Just” “two/too”, “cocktail” “paper/plastic”) augment the pattern:

Finally, there are constructs which, for want of a better term, I call Free Loops, in which the matrix (“Does X have a name”) contains a random assortment of terms, creating an additional sense of tension and surprise that fights against the confining structure.

Patterns of Sound and Sense

So far, I have focused exclusively on the patterns of meaning derived from the words themselves, but of course Schwartz’s poetry is also highly metrical, and the rhythms of her sentences (which are typically very short) follow similar patterns—loops, reversed loops, concatenations, enumerations and elaborations. In this example—which is a kind of skewed variation of the English sonnet (ABAB/CDCD/EFEF/GG)—I adopt a binary digital notation for stressed and unstressed syllables instead of the traditional — and U, because it seems to make the patterning even clearer:

As you can see, 3- to 5-line pattern structures are the building blocks Jenny Schwartz uses to create much larger patterns in which forward action is continually being retarded, then advanced against resistance, then turned and shaped into whorls and arabesques which not only signify but express the ever-shifting interplay of attention and distraction, impulse and inertia, as time hangs heavy.

And it is helpful here, I think, to propose an analogy to music—not in the way that music is all too often invoked in literature, as a justification for sloppy writing—but as a reminder that the patterns here (of meaning and meter) are far more important than the literal sense of the words in conveying what is really going on. Here, then, in schematic form, are the basic patterns of God’s Ear:

Thus armed, it should be possible to follow, in far more detail, a passage like the (fairly astonishing!) opening of Act 1, Scene 5, which consists of five passes through a basic pattern of two sub-loops (the “Four Whys” Elaboration, “I want X for Y/Y is over” Concatenation), with additional optional sub loops:

Patterns of Events and Expectations

The short answer, as I noted at the outset, is “not much.” Ted, the husband, is traveling on business and may or may not be dallying (how wonderful that the word means both “dawdling” and “fooling around!”) while his wife and daughter wait for his return. But in fact two very specific events do occur, and they are responsible for the appearance of the two non-human characters in the play. Lanie loses a tooth at the beginning of Act 1, Scene 1. And in Act 1, Scene 3, Mel decides to bury an action figure she’s stepped on—hence The Tooth Fairy and GI Joe. It is significant that these are both objects that belong to a child. It is even more significant that one is lost, taken away, and cannot be returned while the other is buried, but magically “escapes,” not only coming back but coming to life. Substitute child for object and the meaning becomes self-evident.

Ted, too, returns eventually—but it’s not entirely clear when this happens. Early on in Scene 1, for example, Mel announces “I’m glad you’re home,” to which Ted replies “I’m glad I’m home too.” The scene itself appears to loop through the moment of Ted’s homecoming, and it ends with Ted saying “I came all the way back here and I’ll be damned if I can remember why.” Yet Scene 2 starts with Lanie—awakening in the middle of a night because she’s heard a voice which Mel says is “Dad’s”—being told “Go back to bed and Dad will come home.”

So what has actually happened?

There are various possible quasi-explanations—that Lanie has merely overheard a phone call (but then why would Ted say “I’m glad to be home?”); that Scene 1 is a kind of fantasy sequence; that time itself is out of joint—but here again, I think the most sensible answer is that Schwartz is creating the same kind of loops and patterns with time and causality that she does with language. Ted, in other words, (almost) comes home over and over, just as, out on the road, he (possibly) cheats again and again, until he finally and absolutely does return, and the play can be over. Just as the linguistic patterns of the play delay and advance forward action, so the action of the play itself moves two steps forward and one step back until all the members of the family are finally reunited. As with the profound temporal disorientations and displacements that grief can occasion, so it doesn’t make sense to ask how much actual time elapses in this play. Even though time stands still, virtual events keep happening and unhappening and happening in reverse until finally, magically, time itself—and normal life—can resume.

I will not give away what happens when time resumes, except to say that it involves a memory, and an event—an event which in a sense never happens, yet continues to happen over and over—an event which must not happen, yet did. This is, to be even more specific, a two-act play in which the most important thing that happens is a recollection which, like the lifting of a spell, seems to return us to everyday life, and the promise of a good night’s sleep.

Brooklyn, NY

April 27, 2008